Our Fatigue Risk Management Team help organisations manage the risks associated with fatigue and workload and specialise in delivering fatigue risk management solutions for companies whose employees are involved in safety-critical work, such as aviation, the petrochemical industry, road transport and emergency services. Their work provides organisations with the evidence needed to ensure that the business is operating within an acceptable risk threshold.

For further information on our Fatigue Risk Management Research, Training and Consultancy services contact + 44 (0) 203 805 7792, hello@bainessimmons.com

Summer 2021 has been an exciting time for sport with the UEFA European Championship, Tennis Championships and the Olympic and Paralympic Games in Tokyo. Athletes performing at their best is key to achieving success. Sleep is central to optimal mental and physical performance which is why much interest has been placed on improving sleep in athletes.1

What is the recommended sleep duration for athletes (aged 26 years or older)?

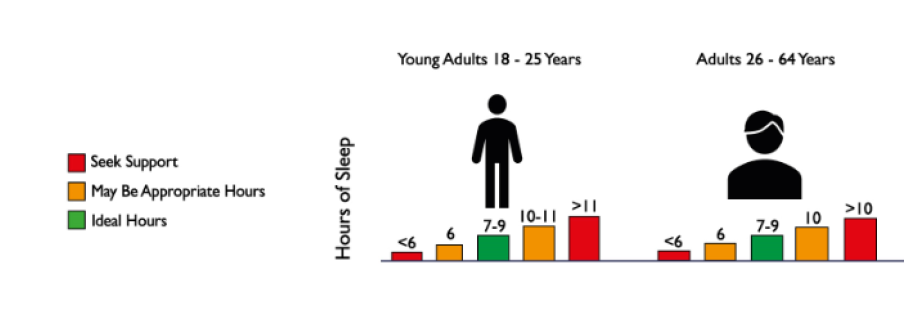

There are no specific sleep duration guidelines for athletes. According to the National Sleep Foundation, the ideal sleep duration for adults aged 18 or more is 7-9 h per night.2,3

Research has found that athletes who regularly sleep the recommended amount have faster reaction times, lower risk of injury and illness and better mental health than those who do not.1,4

That said, sleep loss is common in athletes due to long-haul travel, training schedules and early/late competitions. Cognitive and physical performance are particularly affected in the first few days after travelling across time zones due to sleep loss and fatigue associated with jet lag and long flights.

How do athletes cope with sleep loss?

To limit the impact of long-haul travel on sleep and performance, athletes often begin to adjust to the new time zone a few days before travel.

As a rule of thumb, the body clock takes a day to fully adjust for each time zone we cross. Adjustment is influenced by the timing of light exposure, sleep, and meals. Adjusting behaviour to a new time zone slowly is preferable. For example, by shifting sleep times by an hour each day before departure, e.g., starting a week before travel for a 7-time zone journey for full adaptation. If you’re travelling to the west, try to delay sleep times by an hour, or go to sleep and wake an hour earlier before travelling east. Most importantly, light and dark exposure and mealtimes will have to match this shift in sleep patterns.1 For example, being exposed to bright light earlier in the morning and avoiding light earlier at night before bedtime.

If slow adjustment before departure is not possible, partial adaptation before departure or adaptation after time zone travel can be used. 1,5

Napping and sleep banking are strategies used to cope with sleep loss in athletes.1 Power naps, 20-30 minutes, have been shown to boost mood, alertness and performance.

A recent review and expert consensus paper also recommend sleep banking to enhance sleep and performance before a competition.

Is it possible to bank sleep to enhance performance before a competition?

Research has shown that athletes who are able to sleep longer than the recommended amount, e.g. ‘bank’ or extend sleep by 1-2 hours a night, for a few days ahead of a competition, can optimise their performance.1 For example, compared to when they slept a ‘normal’ and a reduced amount (30% less), cyclists/triathletes who slept longer for 3 nights by an average of 90 minutes (30% more) showed better endurance performance, e.g. 3%, or ~2 minutes across a ~60-minute time-trial performance.6 Further, basketball players, aged 18-22 years, who extended their sleep over a 5-7 week period, e.g. slept as much as possible with a window of 10 hours in bed each night, ran faster in both half-court and full-court sprints and improved their shooting by at least 9% for both free throws and three-point shots. The athletes also reported improved physical and mental well-being.7 The increase in performance generated by sleeping longer for a few days may appear small in some studies3 but small margins in elite sports can make all the difference to winning a medal.

What are the pros and cons of sleep banking, e.g., sleeping 1-2 hours longer for a few days?

Some researchers argue that elite athletes have a higher sleep need than the general population (7-9 h) in order to cope with intense training, competitions and recovery.3 Sleep banking has been recommended for athletes as a strategy to enhance performance but also cope with sleep loss associated with travel fatigue, jet lag, training schedules and competition.1

Beyond elite sport, sleep banking can be used ahead of a period of sleep deprivation for offsetting the associated decline in cognitive performance. For example, a study found that sleep extension improved vigilance and reduced sleep needs therefore the likelihood of microsleeps during the sleep deprivation phase.8 As such, banking sleep would be particularly helpful ahead of a busy work schedule, night work or travel across time zones.

Unfortunately, not everyone is able to extend their sleep unless they are sleep deprived (sleep need is high). Unlike other health behaviours, sleep is not under our direct control which means that effort to sleep may be ineffective at best and disruptive at worst. For example, the risk is that we may spend time awake in bed in the effort to sleep longer and over time the bedroom becomes a source of anxiety as it becomes associated with not sleeping. If you are struggling to fall asleep or you lie awake during the night because of worry and anxiety, please read this information sheet: ‘How to adjust my beliefs and thoughts about sleep.’ 9

What are the benefits of sleep and physical activity for health and performance?

You don’t need to be an athlete to reap the benefits of improved mental and physical performance through better sleep. A good night’s sleep helps us feel motivated and energetic, key ingredients for continuing to be physically active. Sleep also allows our body to recover from exertion. In turn, regular exercise can help us fall asleep more quickly and stay asleep for longer by lowering stress and anxiety levels. A recent review found that regular physical activity can help boost sleep duration, and sleep quality across all ages and improve sleep in adults with insomnia symptoms and obstructive sleep apnoea.10

Many of the effects associated with better sleep are also associated with increased physical activity. For example, both sleep and physical activity:

- Reduce symptoms of depression, stress and anxiety

- Reduce the risk of developing high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity

- Enhance attention, learning and decision making

- Improve immune function

This does not mean that we can substitute physical activity for sleep or make up for lost sleep by exercising. Better sleep improves physical and mental performance, and increased physical activity improves sleep. Therefore, we should nurture both to feel and perform better.

What is the recommended amount of physical exercise per week for adults?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that adults (aged 18 or more) should do at least 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity or at least 75 minutes of vigorous activity per week. Adults should also do muscle-strengthening activities at a moderate or greater intensity that involve all major muscle groups on at least 2 days of the week. In addition, we should limit the amount of time spent being sedentary, e.g. sitting, lying or reclining, by breaking sedentary behaviour with light movement or standing and aiming to do more than the recommended levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity.

When is the best time to exercise?

Exercising outdoor in the morning ensures that you get plenty of natural light needed for strengthening the sleep-wake cycle so that your body is ready to go sleep earlier at night. The combination of morning light and exercise is particularly useful for athletes who are evening types (night owls) trying to reset their body clock, e.g. go to sleep and wake earlier, to minimise sleep loss associated with early morning training.1

If you are not bound by training or work schedules, try to exercise in line with your body clock type11, e.g. if you are a morning type (lark), you will have more energy, and motivation and perform better in the morning. Due to a peak in our circadian rhythm in the later afternoon/early evening, alertness is high which means that performance may be better than for most of us. However, try to avoid vigorous exercise close to bedtime as this will delay your sleep-wake cycle and prevent you from winding down and falling asleep.

How can ‘we’ improve sleep and physical exercise?

Given the role of sleep and physical exercise in health and performance, improving sleep and physical exercise requires a collective effort across different sectors, public and private, e.g. legislation and policy, and across different levels, individual and societal.12 Guidance on sleep duration, e.g. National Sleep Foundation sleep duration recommendations, and education on the importance of sleep and physical activity, are important. So are improving work conditions, access to resources and physical spaces, e.g. opportunity and space to nap to mitigate fatigue associated with sleep loss during night work.

How can ‘I’ improve sleep?

There are also individual actions that we can take to improve sleep. Please read the infosheet ‘How to adjust my daily routines to improve sleep’.13 Since the Covid-19 pandemic, some groups in society have struggled to sleep well, e.g. women and young people, and do physical exercise, particularly outdoors, e.g. if at increased risk from Covid-19 and were advised to shield. Pre-pandemic sleep and exercise routines may have suffered as a consequence and in some cases re-establishing a routine may be difficult as Covid-19 restrictions are eased. If this is your case, please read the infosheet: ‘How to change my sleep habits in order to get more sleep’.14

References

1. Walsh, N. P., Halson, S. L., Sargent, C., Roach, G. D., Nédélec, M., Gupta, L., … & Samuels, C. H. (2021). Sleep and the athlete: narrative review and 2021 expert consensus recommendations. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(7), 356-368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102025

2. Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., Alessi, C., Bruni, O., DonCarlos, L., & Neubauer, D. N. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1(1), 40-43.

3. Ruscitto, C., & Holmes, A. (2019). Am I getting enough good quality sleep?

4. Watson, A. M. (2017). Sleep and athletic performance. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 16(6), 413-418.

5. Booth, S., & Ruscitto, C., (2018). Managing fatigue: Jet lag.

6. Roberts, S. S., Teo, W. P., Aisbett, B., & Warmington, S. A. (2019). Extended Sleep Maintains Endurance Performance Better than Normal or Restricted Sleep. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 51(12), 2516-2523.

7. Mah, C. D., Mah, K. E., Kezirian, E. J., & Dement, W. C. (2011). The effects of sleep extension on the athletic performance of collegiate basketball players. Sleep, 34(7), 943-950.

8. Arnal, P. J., Sauvet, F., Leger, D., Van Beers, P., Bayon, V., Bougard, C., … & Chennaoui, M. (2015). Benefits of sleep extension on sustained attention and sleep pressure before and during total sleep deprivation and recovery. Sleep, 38(12), 1935-1943.

9. Ruscitto, C., & Holmes, A. (2019). How to adjust my beliefs and thoughts about sleep.

10. Kline, C. E., Hillman, C. H., Sheppard, B. B., Tennant, B., Conroy, D. E., Macko, R. F., … & Erickson, K. I. (2021). Physical activity and sleep: An updated umbrella review of the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 101489.

11. Ruscitto, C., & Holmes, A. (2019). Why do some people prefer mornings, and others prefer late nights?

12. Ruscitto, C. (2020). Sleep through the lens of culture.

13. Ruscitto, C., & Holmes, A. (2019). How to adjust my daily routines to improve sleep.

14. Ruscitto, C., & Holmes, A. (2019). How to change my sleep habits in order to get more